2018, After, before, yesterday, meanwhile, now, you, me, those, the others, right and left

Daniel Faria Gallery, 2018

After, before, yesterday, meanwhile, now, you, me, those, the others, right and left

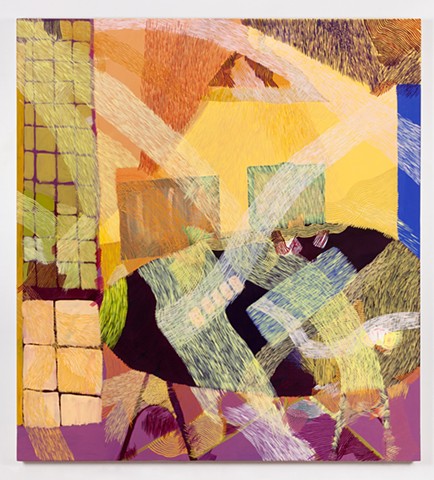

Standing in front of Dad’s dresser and lamp with picture of his father, I get fixated on a hint of ochre underpainting beneath a frenzy of Derek Liddington’s lime and citron brushwork. The déjà vu is uncanny. I close my eyes and immediately hear the way a handle clacks its faux brass finish against the stopper while I secretly slip a drawer closed, having just riffled through a pile of softly folded underthings. This scene is brown, it’s cream, it’s tan and orange. I sense the flimsy roller blind that has been engaged to shade out the south-facing sun and can make out the soft chatter of the television in the next room. I smell the used Melita coffee filter laying limp and soggy in the kitchen sink downstairs. And yet it is the drawer handle I’m fixated on; its patina worn from years of oily fingertips grasping and grazing it, tugging it to slide the glossy mahogany drawer in and out, to extract and later return the over-washed cotton garments, folded along the same worn lines, over and over again. I sense the languid, rubbery nature of the large leafed vine that droops just within my grasp, and almost taste its chlorophyll centre as my thumb presses it, digging my bitten fingernail in, so that the waxy residue lives for a while underneath its gnarled edge. I try to focus on the entire room and the image disintegrates, breaking into shards of what it isn’t: fragments beyond my reach. I’m trying to tell you why this place is important to me. But I can’t use my voice. It’s the screen behind my eyes that I’m trying to make you see.

These types of sensorial evocations are at the heart of Derek Liddington’s recent body of work. Using paint as a means to layer physical, temporal and emotional associations he has with particular domestic spaces, Liddington’s canvases capture the intimacy of these places, as well as the way his remembrances of them play out in his mind. Basing his palette on a synesthetic response to each scenario, the artist grounds the paintings with a recognizable item – a porcelain bust, a tarnished piece of jewelry, a framed photograph – before splintering it into a kaleidoscopic flurry of his signature mark making. These brushstrokes act like adverbs, modifying or amplifying the passage of time, motion in the memory, or the impression of the event. The specifics of the scene remain below the surface and we the viewers are left to feel the echo of their trace, rippling before us like a cloud of the thing they once were. Here, Liddington asks how ephemerality can be coaxed into standing still, how gesture can be retained in two dimensions, and how seemingly prosaic recollections come to retain a lasting effect.

-Rhiannon Vogl